On the higher fertility of semiconductor workers

One in every fifty Taiwanese babies born is a TSMC baby.

This tweet has gone viral for pointing out the extraordinary fertility of the employees of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), the world’s leading manufacturer of semiconductors and producer of nearly 90% of the most advanced chips. Though TSMC employees make up 0.3% of Taiwan’s population, they are responsible for 1.8% of all babies born in Taiwan. In every fifty Taiwanese babies born, one is a TSMC baby.

The seemingly enhanced fertility of TSMC employees is of great interest because Taiwan is one of the world’s ultra-low fertility countries, with a Total Fertility Rate of 0.87 children per woman (meaning every 100 Taiwanese people will have a total of 8 great grandchildren between them).

So why might a worker at TSMC be more likely to have a child? I propose that TSMC’s own policies are boosting birth rates at the company in two connected ways.

Policy and the culture it makes

We only know about the higher fertility of TSMC employees because TSMC themselves proudly announced it earlier this year.

TSMC is striving to be a family-friendly workplace, with the latest efforts currently being spearheaded through the TSMC Child Care Benefit Program 2.0. Childcare is offered to employees from 7am to 8pm. Each of the company’s four campuses have a preschool for children aged two to six, boasting a curriculum that includes “Immersive Food and Agriculture Education”. There are also half-day science camps on the weekend. There are photos on TSMC’s website of employees’ children learning how to make kumquat tea and visiting a dried persimmon factory.

For the parents of infants, there are flexible shifts and lactation rooms for breastfeeding or pumping. For expectant mothers there is a sliding scale of maternity leave, with 12 weeks for the first child, 16 for the second and 20 for the third.

I argue these policies have two birth boosting effects.

One, the company’s policies have successfully made their employees more likely to have children simply by making it easier for them to do so. Consider that if you are a TSMC parent you pay nothing for very high quality childcare that is conveniently located at your very workplace. You also work for a company that is regularly signalling to you that they support you having children and that parenthood won’t negatively impact your career. In fact, your company is even saying this publicly, to the media, making the signal even stronger.

Second, in TSMC’s policies successfully lowering barriers to parenthood, these policies have initiated a positive feedback loop between employees. Peer transmission effects on fertility have been observed among teenagers and a negative effect was recently identified by an Italian study, which found that a single percentage-point decrease in average co-worker fertility led to a reduction in the individual probability of having a child of 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points.

In successfully encouraging more of their employees to become parents, TSMC employees are being affected by positive peer transmission effects. These are generated simply by knowing more parents of young children or by seeing a colleague combine work and parenthood without difficulties. This has the effect of encouraging parenthood, because peers demonstrate that having children is achievable and positive. In short, the policies have initiated a self-propelling culture of parenthood.

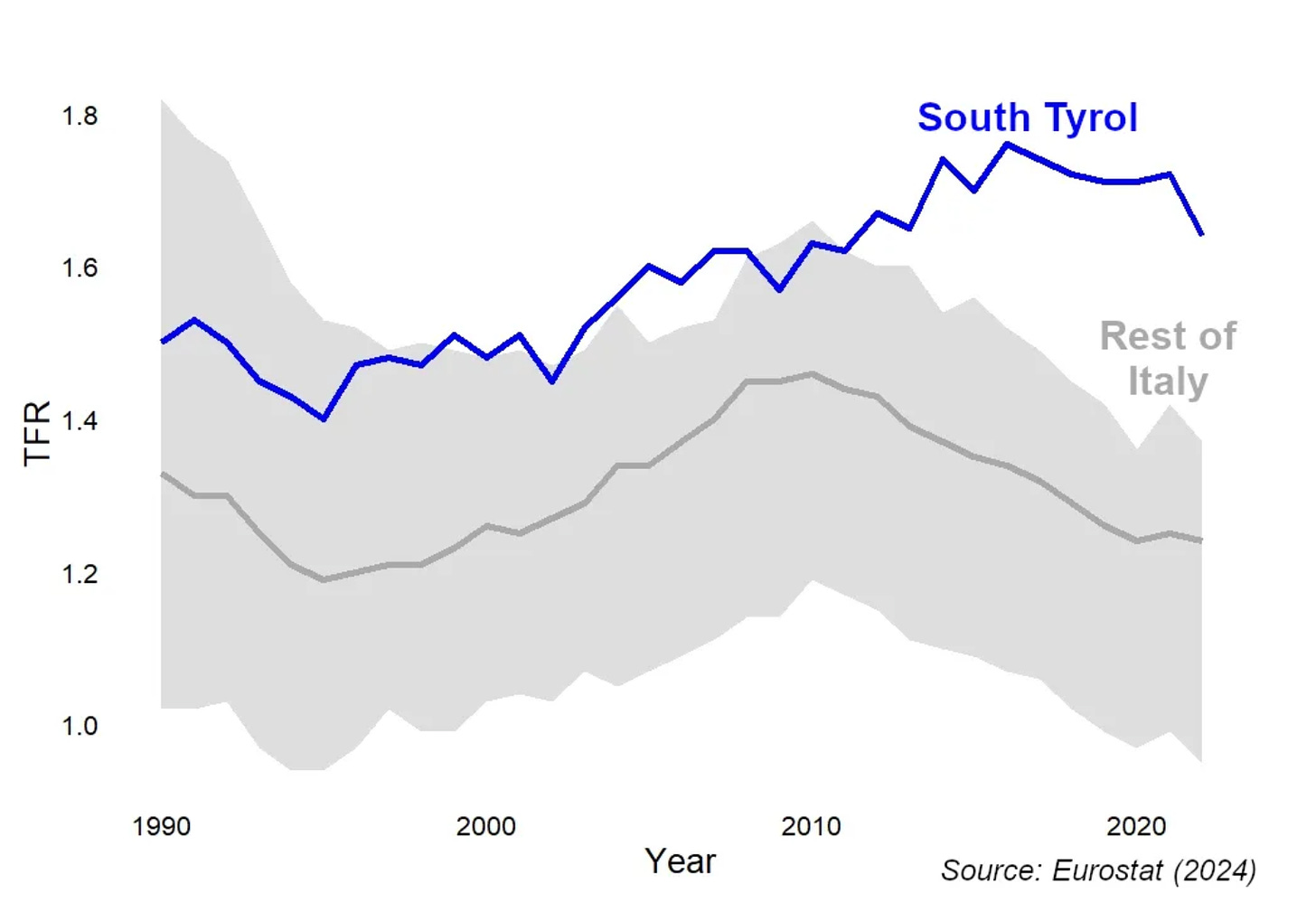

Boom has previously written about the case of South Tyrol, the province defying Italy’s birth dearth. South Tyroleans have enjoyed thirty years of practical, child friendly policy making that much resembles TSMC’s in spirit. There are public transport and supermarket perks for families. There is a highly functional, affordable and easy-to-access childcare system.

And as with TSMC employees, in South Tyrol the child-friendly effects of these policies may be strengthened through reverberating peer transmission effects. South Tyrol’s policies have better supported those who have children and who have larger families than in other Italian regions. That means that younger South Tyroleans are more likely to be familiar with larger families, and to be familiar with people who have had children earlier in life than the Italian average. This is very likely to make them more likely to consider these options for themselves.

I think a combination of the practical benefits of the policies instituted by TSMC and the culture then created by peer transmission between co-workers is a major contributor to the boosted fertility of TSMC workers. But there are also other characteristics of working at TSMC that are likely relevant.

Working at Taiwan’s most profitable company

Taiwan makes 65% of the world’s semiconductors and TSMC, which is Taiwan’s most profitable company, produces most of them. Workers at TSMC know that they are working at the leading company of an industry that accounts for 15% of their nation’s GDP. Their skills are in demand, they are well remunerated, and enjoy many perks that exceed Taiwan’s statutory requirements, such as extra annual leave and paid sick leave.

In response to the TSMC story, demographer Lyman Stone pointed out that chance of parenthood and status are positively correlated for men, globally. At Boom, we’ve touched on this effect when writing about Finland: across the Nordic countries, those most likely to be childless in society are men of a low education level. In having a socially useful, well paid job, TSMC workers are likely receiving a fertility boost, because it is easier for them to set up their own household and to partner.

We also know that individual financial uncertainty depresses birth rates, while individual financial certainty increases them. Because of their in-demand skills and the nature of their work, TSMC workers may be more sure of their position and their earnings than other types of employees in Taiwan, also making them more likely to start a family or have another child. There’s evidence that other tech workers in Taiwan are benefitting from a similar effect.

Others have written how Hsinchu, the city which hosts Hsinchu Science Park (including a TSMU campus) and is known as Taiwan’s Silicon Valley, has the highest average household incomes in Taiwan and is enjoying a mini-baby boom, a ‘prosperous family phenomenon’. Hsinchu City and Hsinchu County are the only prefectures of Taiwan where the under 14s outnumber the over 65s. In Guanxin Village in Hsinchu, where 90% of residents work at the Hsinchu Science Park, under 14s account for 29% of the population, as opposed to 11.9% in Taiwan overall.

Note on potential demographic confounders

Finally, though TSMC’s announcement is impressive and interesting, more data would be useful. Ideally, we’d have a Total Fertility Rate calculated for TSMC employees and I would prefer a statistic that accounts for the fact that Taiwan is an ageing society and that the employees of TSMC are going to skew young, and therefore be more likely to become parents.

But relevant in indicating that there is a TSMC or tech company baby boost that goes beyond simply having younger employees is that Hsinchu County has the highest child dependency ratio in Taiwan, with more children per 100 working age adults than in any other region. Hsinchu County’s child dependency ratio is 27.7, as opposed to 16.4 in nearby capital Taipei City and 19.7 in New Taipei City.*

Conclusion

TSMC workers are parents to one in every fifty Taiwanese babies for three reasons. Because they: work in a company with policies that actively make parenthood easier; are influenced by the pro-parenthood culture that has consequently developed between peer colleagues; and are prosperous, with stable and well paid jobs.

Phoebe

* The content in the note on demographic confounders was expanded and given its own section following a useful comment from Jonathan Portes.